Smaller companies are due their time in the sun

Last year smaller companies once again underperformed the market in part because the US tech mega-companies cast a long shadow. The ‘Magnificent seven’ swept all before them and there was little escape from the cold. Small-cap sentiment is poor, the economic and geo-political backdrop has been volatile, and valuations have again suffered despite the sector’s good earnings record. Yet, the backdrop is about to change for the better and early indications suggest sentiment may be improving. With valuations looking attractive, we have been increasing our portfolios’ exposure while retaining a focus on quality companies in this still challenging economic environment.

Elephants don’t gallop (for long)!

The case for smaller companies is well rehearsed – they have tended to generate higher returns over time. For example, since 1955, the Numis Smaller Companies Index excluding Investment Companies (NSCI), which represents the bottom 10% of the UK market, has beaten the FTSE All-Share index on average by c.3% per annum. There is an inherent logic to this. Smaller companies tend to operate in niche and growing markets and exhibit faster growth in part because they are benefiting from the advance of technology. This is not just helping to reduce costs and open new markets but is better enabling them to increasingly embrace the disruptive practices needed to compete with their larger brethren.

Apart from the increasingly rare pockets of excellence, including the ‘Magnificent seven’ and those UK companies capitalising on the opportunities proffered by data, the absence of genuine entrepreneurship in many of the world’s larger companies, together with an adherence to a financial system too focused on the short-term, have contributed to their underperformance. My column ‘Where are our pioneering giants?’ (8 February 2019) touches on this theme in more detail. As with investments generally, investors need to be invested for the long-term to capture this smaller company effect. The fact these companies exhibit greater volatility can then be embraced as an opportunity, such as is the case now.

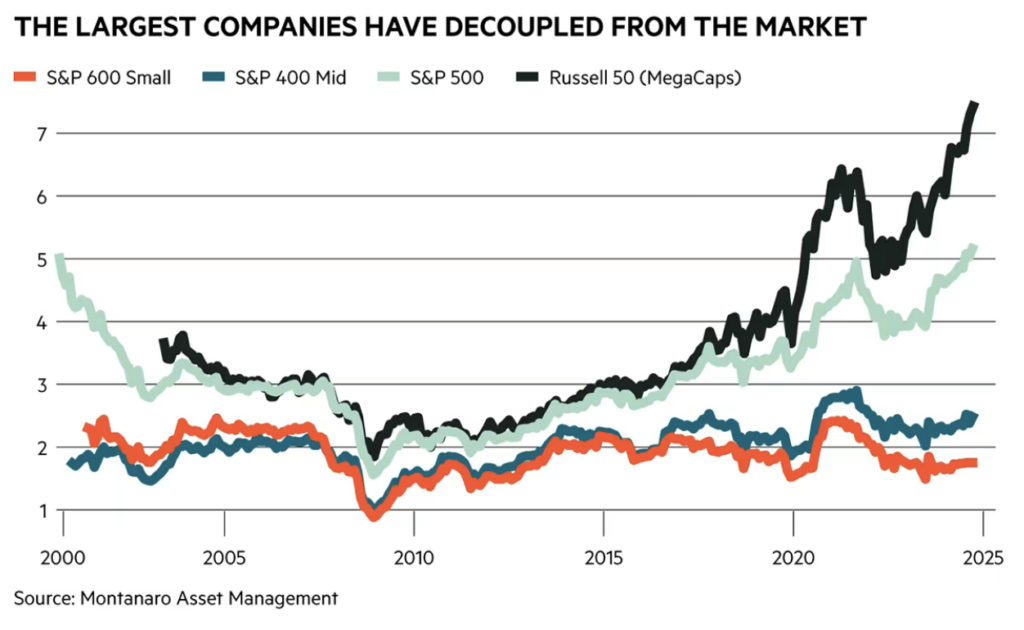

Part of this reasoning is down to caution regarding the mega-caps’ ratings. No one doubts the potential of AI, and the challenges and opportunities alike, but valuations still matter when it comes to portfolio management. The graph below highlights the extent to which the largest companies have decoupled from the rest of the market – Price to Book (12m trailing). Those of us long enough in the tooth can remember previous tech bubbles and how they ended – with ‘reversion to mean’ reasserting itself. It is very seldom ‘different this time’. It is no coincidence that the portfolios are underweight these mega-caps at a cost to short-term performance, but we remain steadfast in our belief that better risk-adjusted opportunities exist elsewhere.

For example, although US small cap share prices have lagged the wider market in recent years, they have grown their earnings faster than the S&P 500 index. This speaks to the ‘concentration’ effect of the very large tech companies – with recent figures showing Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and Nvidia accounting for c.19% of the MSCI World Index. The focus on these mega caps, reinforced by ETF buying, has shifted investor attention away from smaller companies. Just as similar periods of market concentration in the early 1970s and during the tech boom in 2000 were followed by a period of strong outperformance by small caps as sentiment shifted, the omens look similarly good now.

Certainly, the outlook for US smaller companies has improved given the election result. Trump’s decision to scrap the planned increases in corporate taxes from 21% to 28%, his programme of tax cuts and deregulation, a better economic outlook, and the advent of further interest rates cuts, in combination will disproportionately help smaller companies. We will wait to see if the increased use of tariffs materialises, but these companies are less exposed to the volatility of global trade and may benefit from the supply chain opportunities that will arise should more companies ‘onshore’ their manufacturing back into the US. As such, the small cap sector looks to be in the foothills of a strong period of outperformance.

And therein lies the opportunity for the contrarian investor. In the US, the price/earnings ratio of the Russell 2000 has usually traded on a 25-30% premium to the S&P 500. Today they are within touching distance of each other. It is a similar story globally. On a Shiller price/earnings measure, UK small cap valuations are standing on c.15.5x earnings – the range over the last 40 years being 12x to 28x. Attractive valuations elsewhere include Europe where they are unduly depressed. Allied to reasonable investment trust discounts and experienced managers with good track records and appropriate levels of gearing, one senses sunrise is on the horizon.

However, attractive valuations do not in themselves beckon better times. There may be straws in the wind as to possible catalysts. A nuanced but perhaps important observation is that recently smaller companies have tended to be resilient when the mega-caps have faltered. This may reflect growing concerns about market concentration and valuations providing a measure of safety, but it suggests small caps are becoming more important as a means of diversification. Meanwhile, evidence suggests M&A activity is on the rise which again speaks to attractive valuations at a time when institutional investors are looking to increase their exposure, and private equity continues to seek a home for its cash piles.

Quality must be the byword. Small caps usually perform particularly well as recession fades into memory, interest rates fall, and inflation is tamed if not beaten. Some analysis of the US suggests on average a sector outperformance of 15% over the following year, which in part reflects an anticipated nimbleness in capitalising on the improving outlook. However, the current economic environment will not be without its challenges. Although growth in the US is expected to be better given the economic agenda, elsewhere it will be more fragile and unpredictable for various reasons. Furthermore, the speed of interest rate cuts will be more pedestrian than some would like.

The column ‘Preparing for inflation’ (12 March 2021) highlights why inflation globally will be more persistent and volatile than hitherto – three will become the new two. We have indeed reached the end of cheap labour, cheap capital, cheap energy and resources, and cheap goods. Financially weak companies will be disadvantaged, particularly if economic growth splutters. It will be important to focus on companies with strong balance sheets, experienced managements and markets where the company may have an edge – even if such companies stand on a warranted price/earnings premium to those less fortunate. More resilient earnings in volatile times tend to make for better total returns over time.

Saba shakes

For the moment at least, Saba Capital has been seen off the field. It has lost all seven votes. Boards have succeeded in rousing retail shareholders. Yet there is no room for complacency. This has been a wake-up call for some companies to be more proactive in closing wide discounts and to improve their communication with shareholders – many of whom were alienated by the nature of Saba’s initial approach. It may have done better had it instead deployed its current tactic of now offering shareholders of CQS Natural Resources Growth & Income (CYN) and others liquidity close to NAV. But then again perhaps not. Saba underestimates the rationale of investment trusts – to invest much-prized long-term capital and deploy gearing courtesy of their structure, thereby producing superior returns over time. This is a sector which spurns short-termism – as Saba is again likely to find out.

Return to News